liminal (adjective): between or belonging to two different places

Multi-disciplinary creative Leah Jing McIntosh says she’s prone to getting into trouble. Art, to her, is a provocative agent of change to disrupt and challenge colonial narratives and awaken new landscapes of imagination.

“I’ve always felt troubled by the idea of purity,” McIntosh says. “Which is funny, considering my middle name, Jing, means ‘pure’ in Chinese.”

As an Asian-Australian woman, McIntosh seeks to dismantle prejudiced ideas of purity and value. A writer, editor, photographer, researcher and activist, she critiques Eurocentric Australian culture by championing voices that occupy liminal space.

Stories have always played a significant role in McIntosh’s life. She completed her undergraduate degree in literary studies at Monash University, and gushes over how wonderful it is to read for course credit. But she then relocated to the United Kingdom to study a Masters of English Literature at University College London—retrospectively, a career turning point. In her course on influential contemporary literature, McIntosh was disturbed that only one author was a person of colour.

“I didn’t realise how angry I was,” McIntosh says. “[But] I started to get more angry [as] the lack of diversity and inclusion really started jumping out.”

McIntosh built her thesis around the complex relationship between landscapes and the physical body. Her research focused on Asian-American poets, who, in penning their own stories, rewrite their bodies into the American landscape they are excluded from. In this way, McIntosh uses her work to highlight literature’s potential to challenge discrimination.

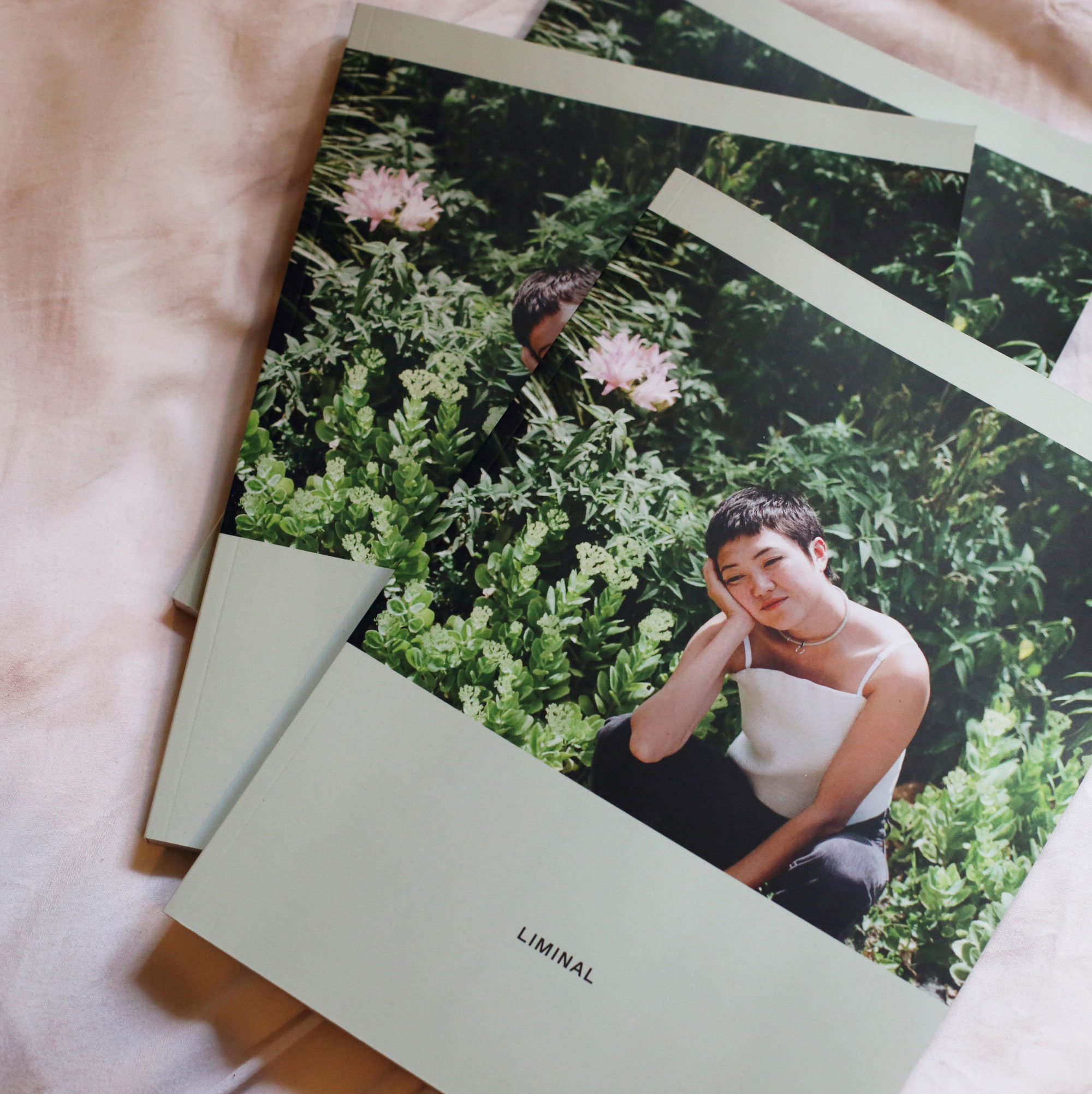

Trouble is never far away. When she returned to Melbourne, McIntosh felt similarly estranged. Driven to expose racial inequality and dismantle literary forms that silence marginalised voices, in 2016 she founded Liminal, an “anti-racist” literary journal. McIntosh, as editor, says its diverse work contributes to “a more equitable arts sector” as it “speaks to what it means to be othered or minoritised bodies in Australian space” and counters the under- and misrepresentation of Asian-Australian experiences in mainstream media.

Liminal now consists of over 190 interviews and portraits of talented Asian-Australian creatives and activists, a serialised anthology for comics artists, and several series of art and writing. It’s an exceptional online platform for individuals “cracking open [the] concept of what Asian-Australian is, [and] also cracking open [the] concept of what literature is” by asserting the value of non-traditional expressive forms like experimental poetry and interactive video games.

But Liminal also encourages white Australians to empathise with others’ experiences by providing a glimpse into new worlds. Liminal, and art generally, McIntosh explains, is

“a gentle way … to provide an argument for [the] humanity” of Asian-Australians.

It’s uncomfortable to confront the necessity of such action, but McIntosh is deeply disheartened by rising anti-Asian hatred during the COVID-19 pandemic and the appalling police brutality surrounding 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests. It’s clear that the world desperately needs McIntosh to keep making trouble by platforming anti-racist voices.

These troubling themes are also the subject of McIntosh's research as she completes her PhD in Cultural Studies at the University of Melbourne. Her thesis centres on the “anti-colonial” potential of Asian-American autofiction—works that combine autobiography and fiction—to break traditions of form, truth and literary value. Through works by Ocean Vuong, Alexander Chee and Jenny Zhang, McIntosh is exploring how hybrid genres create space for marginalised stories.

When I ask about her future plans, McIntosh is understandably apprehensive. “Have you been talking to my mum?” she laughs. Liminal has just announced a major nonfiction prize for First Nations writers and Australian writers of colour. The long-listed entries will become an anthology published next year. However, McIntosh’s academic future is less certain. Ideally, she’ll continue conducting “anti-racist” research while working on her first manuscript. “They’re pretty tangled,” she says of her research and artistic practice. “I don’t think I’ll ever be able to pull them apart.”

To me, McIntosh represents hope for a future in which humanities scholars continue to invest in research with meaningful social consequences. Research that might change the world. The humanities, McIntosh says, “give us a way out” of the mess we’ve landed ourselves in—the environmental disasters, systemic oppression and social injustice. “I think the arts allow us to search for a joy,” she explains.

There is undoubtedly a joyfulness to Liminal, which continues to unearth voices that might steer us towards a more sensitive and egalitarian future.

“The humanities make life worth living,” McIntosh says. “They provide a scaffolding for society and for community that isn’t just one of utility, that isn’t just one under the dictates of capitalism.”

Art and the humanities transform how we think about ourselves and our culture, allowing us to glimpse others’ perspectives and challenge oppressive systems. This pursuit underlies Leah Jing McIntosh’s trouble-making art and research; she reimagines our cultural landscapes to envision a more joyful future.

Find out more about Liminal by visiting their Twitter or Instagram pages.

Article by Lucy Turner

Lucy Turner is in her third year of a Bachelor of Advanced Humanities (Honours). She is completing a major in English Literature and hopes to use it to help bring other people’s inspiring and thought-provoking stories into the world.

Published: 27 October 2021