“A partnership approach could change perceptions about police legitimacy and improve understanding about why police exercising their powers helps to keep communities safe.”

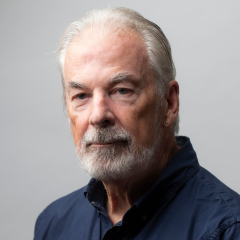

Professor Lorraine Mazerolle enables policy makers and police departments around the world to understand patterns in crime interventions so they can make evidence-based decisions for preventing crime and reducing its impact, and by doing so keep their places on the planet safe.

Her contribution to criminology research has been acclaimed internationally, with over 10,000 citations, more than 60 grants, high demand as a panellist and keynote speaker, and numerous achievement awards.

Last year she was listed by AcademicInfluence.com as one of the 10 most influential criminologists of this century.

Professor Mazerolle’s recent focus includes the complexity that COVID-19 has added to police work.

She has co-authored several papers published this year relating to the pandemic’s impact on crime and policing, including in such prestigious journals as Nature Human Behaviour, The Australian Economic Review, and the International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice.

Professor Mazerolle also presented on ‘Policing Health Regulations during the COVID-19 Pandemic’ at the Asian Criminological Society’s 12th Annual Conference in June.

“Enforcing lockdown restrictions, communicating with masks on, and maintaining physical distance while interacting with potential offenders on the street are just some of the ways police are having to adapt their practices,” Professor Mazerolle said.

“Stay-at-home orders have interrupted usual crime patterns in residential burglaries, while less-used commercial buildings become easier targets, so directing where to patrol has had to be reconsidered.

“But while restricting mobility in the community is associated with a significant drop in urban crimes like theft, traffic offences and alcohol-fuelled violence in public, the types of crime that have declined or escalated has varied in cities around the world,” she said.

As an experimental criminologist, Professor Mazerolle’s work involves randomised controlled trials in the real world and systematic reviews of the literature to inform criminal justice policy and practice.

This includes testing assumptions about crime-reduction factors and correlating them with evidence captured in a unique web-based and searchable global database she helped establish in 2015.

The Global Policing Database (GDP) is a systemically compiled and reviewed source of published and unpublished experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations of policing interventions conducted around the world since 1950.

Police, researchers, social welfare practitioners, and policy makers use it to access a wide range of options, including interventions that target problem people, situations and places.

The GPD was developed at UQ with colleagues from Queensland University of Technology and received funding from the UK College of Policing and Professor Mazerolle’s ARC Laureate Fellowship.

“What makes the GDP distinct from other policing research repositories is that it captures evaluations of interventions conducted by police, with police and on police,” Professor Mazerolle said.

“It goes beyond looking at crime and disorder outcomes to collecting studies about fear of crime, perceptions of police, organisational effectiveness, physical and mental wellbeing, and more.

“It includes interventions that address the needs of victims and that develop professional practice.

“This coverage is important for understanding why policework involves more than preventing or responding to crime, and why making decisions about policy, procedures or funding shouldn’t be based on statistics alone,” Professor Mazerolle said.

Hot spots policing, for example, is a data-driven strategy involving police working alone to target very micro places of drug problems.

A recent review for the Australian Institute of Criminology, which drew from the GDP, revealed that hot spot policing for street-level drug law enforcement is not as effective as when the police work in partnership with others, such has hoteliers, business leaders and schools.

Police partnerships are at the core of another of Professor Mazerolle’s innovative research projects.

The Ability School Engagement Partnership Program (ASEP) brings together communities, schools and police to tackle the problem of school truancy.

Professor Mazerolle and her colleagues have been tracking the 10-year collaboration between Queensland Police and the Queensland Department of Education, one that engages young people, their parents, teachers and police to empower rather than punish at-risk students.

The program was established through Professor Mazerolle’s ARC Laureate Fellowship and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (the Life Course Centre), which investigates generational disadvantage within families.

ASEP involves police and school representatives meeting informally with the student and their parents to talk about truant behaviour and its consequences, such as explaining the legal responsibilities of parents to ensure their children attend school.

Together they decide on a course of action to enable the young person to re-engage with school. This might include new home routines, additional tutoring, or accessing support services to address psychosocial issues.

“Kids who skip school are more at risk of being snared into antisocial behaviour, and have more potential for negative life outcomes than young people who don’t skip school,” Professor Mazerolle said.

“Our research showed that harmonising the way that police and school authorities engage with young people can disrupt the relationship between truancy and delinquency.

“The research also highlighted how a partnership approach could change perceptions about police legitimacy and improve understanding about why police exercising their powers helps to keep communities safe.

“The students who participated in the active program were more willing to go to school, attended school more often, offended less, and self-reported less antisocial behaviour than in the control groups.”

Professor Mazerolle admits that as an adolescent she didn’t understand how people could commit harm.

As an adult, she has devoted her career to analysing the factors that influence crimes and criminality, applying the objectivity of numbers through the lens of social science to help make the whole world a safer place.